Improving Accessibility in Outdoor Recreation

Adaptive athlete Brandon Mantz on how the RV industry can help make the great outdoors accessible for all.

When Brandon Mantz woke in the trauma center of St. Anthony’s Hospital in Lakewood, Colorado, he couldn’t speak.

A tube emerged from his mouth and his brain was foggy. He wasn’t yet aware he had broken ribs, punctured lungs and a fractured shoulder, and — if he hadn’t been rescued in time — enough internal bleeding to threaten his life.

“The first thing I remember is the doctor telling me that I was in a ski accident, I was paralyzed and that I had a zero percent chance of ever walking again,” he says.

It was December 2018 when Mantz, an avid outdoorsman who had just moved to Colorado from Wisconsin, headed up to Breckenridge to hit the slopes with friends. Early in the season, a light dusting of snow covered the ground as the group tackled a few greens and blues before driving back to Denver. On the day’s last run, his friends skied ahead as Mantz gained speed and abruptly smacked into a trail marker post. The group didn’t see the crash, and he doesn’t remember it himself, he says. Details came days later when a retired surgeon, who was skiing behind Mantz, visited him in the hospital.

“[He said] he saw me right away, started medical protocol and called ski patrol. He said that I was spitting up blood, but that I was conscious and responding back to him,” he says.

When ski patrol arrived, the Flight for Life helicopter was dispatched to pick him up mountainside. Mantz spoke with the flight crew nearly two years later.

“They said there’s maybe two days in a whole year that the conditions are good enough where they can pick somebody up from the mountain, rather than transporting me down on a snowmobile and then going to a helipad in Breckenridge,” he says. “So, if it didn’t happen so fast and they weren’t able to pick me up, I probably would have bled out.”

Mantz lost 3 liters from internal bleeding, requiring immediate blood transfusions and intubation. When he stabilized, he learned of his complete spinal cord compression. There were zero signals the doctors could see going past the injury point, Mantz says. He recalls being thankful for his doctor’s sincere honesty.

“[He said] ‘The best thing you can do is rehab and start figuring out what life is going to look like in a wheelchair.’”

After three weeks and a Christmas in the ICU, Mantz transferred to Denver’s Craig Hospital — one of the country’s top brain and spinal cord injury rehab facilities, where he spent another eight weeks.

He had always been an athlete, having played college baseball and, post-university, spent time skiing, trail running and biking outdoors.

“[After the accident], it was learning how to get dressed again, navigate in a wheelchair and what it was like to brush my teeth not having the ability to stand over the sink,” he says.

Mantz had no choice but to learn, and eventually advocate for, how to live in a completely different way.

Pursuing Possibility

When he started his recovery, Mantz worked for a power conversion company adjacent to the RV industry, whose long-term disability policy allowed him six months before returning to work. Fortunately, he had a remote position and didn’t need to worry about a commute.

“For a lot of folks that have an injury and become disabled, reentering the workforce is really challenging. There’s a lot of logistics like learning to drive in a different way — or maybe you can’t drive at all,” he says.

Accessing public transportation isn’t always easy with a disability, he adds. Neither is navigating work travel.

“But at Craig Hospital, they have a driving program, so I learned pretty quickly how to drive with hand controls. I got portable controls, too, so whenever I traveled for work, I could get any rental car and install these portable hand controls myself.”

His suitcase hooks onto his wheelchair so he can navigate airports independently. But until a few mentors showed him what was possible, Mantz says traveling seemed out of the question.

“I think this is why representation is so important. If it wasn’t for people like Justin [a peer mentor at Craig] who visited me in the hospital and showed me pictures of him backpacking through Europe in a wheelchair and doing things like camping and hand-cycle mountain biking, I wouldn’t have had any idea of what was possible.”

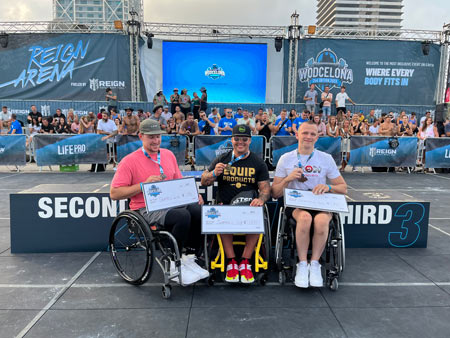

Mantz connected with a group of four disabled athletes in Denver, all with spinal cord injuries.

“We were having dinner, and it was like, you know what? We may have met because of the wheelchairs, but it’s the things we like to do that bonded us. We can go out and ride mountain bikes, do a CrossFit workout or go skiing together. Those experiences turned us into friends.”

While he wouldn’t wish the experience on anyone, Mantz says his personal growth has blossomed over the last five years. At the forefront was learning to accept himself as someone with a disability.

“I was kind of burying a lot of emotions,” he says. “So, doing a lot of that work in how I navigate the world, I realized it’s almost never the physical — it’s the mental and emotional behind it. Like, I’m frustrated that I can’t have the same experiences as my able-bodied friends. It’s not that I have to push a wheelchair; it’s the feeling that I don’t have the chance to be close to them through specific experiences.

“I think an important thing is to have experiences that everybody can participate in. It’s awesome that there are organizations that connect specific populations, like veterans or wheelchair users or amputees. But it’s also important to have the general population be able to access something together. Like, could my friends going camping in their RV even invite me to go with them?”

Accessibility goes far beyond personal impact — it’s about multiplying the reach, he says. Everybody knows someone who can benefit from better accessibility. Without the integration piece, where people with different abilities and disabilities can do things together at an equal level, Mantz says “we’re just back to segregation in a different way.”

Reframing the ‘Rare Case’

Across the board, representation in the outdoor recreation industry is becoming crucial to consider for the market’s future. And while race, age and other factors are important to discuss, representation for those with disabilities has largely been left out of the picture — despite 1 in 4 (27% of adults) in the United States having some type of disability, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“That piece is so huge for somebody that has a life-changing experience or injury,” Mantz says. “And this could go way beyond disabilities — this could be for a family that has a baby for the first time, who’s like ‘we loved RVing in the past, but I have no idea how this will work with a baby.’ It’s to have other young families they can look to. Or if I’m a person of color and I think the outdoors isn’t for me because of the underrepresentation.

“To see other folks that look like you outdoors — it can make you say, ‘Oh, I can be part of this and have an awesome experience like this, too.’”

In the shifting RV industry, a hot topic is how to attract and retain more people (and more customers) in outdoor spaces. Much of the answer is engaging new demographics, which Mantz says includes reframing what “accessible” means.

“If we have that representation and we start to make accessibility more of a baseline, then you’re going to see more people out there doing it,” he says.

It’s easy for businesses to think about accessibility as the “rare case” that can be accommodated with custom builds. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) — a 1990 civil rights law prohibiting discrimination based on disabilities — serves its purpose, but Mantz says many would agree there are gaps that don’t address today’s functionality needs. Oftentimes ADA-compliant bathroom stalls have doors that open inward, not allowing enough space for a wheelchair to pull through and shut the door. Some accessible entrances or routes are through the back of a building and don’t give the same experience to people with disabilities. Buildings with less than three stories aren’t required to have an elevator. And even ride share apps like Uber aren’t covered under the ADA, so drivers can refuse a ride to a passenger with a disability.

“In general, the ADA is reactionary and not preventative. A person needs to file a formal complaint of an ADA violation for action to occur, rather than preventing these barriers in the first place,” Mantz says.

“I like to think of it as, what simple changes would benefit the majority of the population? If I’m an RV manufacturer, I have my ADA model, which is great, but how can I make my standard models with a wider galley for a wheelchair or stroller to fit through? Do I have a preplanned place where I can add a ramp or lift to an existing model? Or maybe it’s an aftermarket upgrade — but those things are thought about ahead of time. It’s not this one-off custom project.”

The same goes for RV dealerships — can salespeople provide the same service regardless of a customer’s abilities? Pre-1990 buildings don’t have to be ADA-compliant and often don’t have accessible entrances. From a hospitality standpoint, when an RV business looks at how to greet and keep a customer, mission statements often mention making them feel like family to provide lifelong memories.

“If you’re saying things like that, you should look at the experience from a lens of accessibility as well — that you’re giving everybody the same opportunity to make those memories.”

At one of the industry’s largest annual shows, Mantz doesn’t remember seeing any accessible RVs on the floor — and could barely peek inside the open doors of typical units. Whether a dealership or manufacturer, he says it’s vital to have accessible models on the lot so customers of all abilities can see what’s possible.

RV rentals are another opportunity to bolster the market, often serving as a pathway to attract buyers into the industry.

“But if there’s not that many accessible rental models, how do I try RVing out? I have to go buy a custom RV — and then maybe I take it out and realize it’s not for me. That’s a huge barrier to entry.”

With outdoor recreation generating $1.1 trillion in economic output in 2022, making the great outdoors accessible for all goes beyond the $140 billion RV industry. Areas such as campgrounds also have room for improvement. Some locations only have one or two accessible campsites available — and if they happen to be booked, those with disabilities are out of luck.

“If campsites were all accessible, that doesn’t mean people who don’t have accessibility needs couldn’t use them. It would still provide a great experience.”

Keeping terrain wild is part of the conversation, Mantz says, rather than opting for unnatural landscape changes such as adding chunky gravel.

“Where we’re altering campgrounds and other outdoor areas, we can make choices for accessibility. If we’re leveling terrain, make it flat, use a fine gravel or paved surfaces that are easier to move through.”

For amenities, especially bathroom facilities, it is fundamental to make accessibility standard. If everyone can use an ADA-approved bathroom, what’s stopping more stalls from being accessible? Rethinking accommodation isn’t about benefitting a minority group — it includes families with strollers, the aging population and more.

“I think about my grandparents specifically. When I’m doing things with them, I’m not the limiting factor. They’re not able to do a lot of stairs, and walking on uneven surfaces is challenging for them. But they love being with family and being in the outdoors and would totally do it more if they could,” Mantz says.

Despite multiple areas having room for improvement, he notes one thing those with disabilities understand is not everything can change all at once. The biggest opportunity is rethinking how things are done moving forward, especially when it comes to landscape shifts such as electric vehicles and sustainability.

“Where we might be adding more [EV] charging spaces, can we make those accessible? It’s hard to change something, but if we build it accessibly from the start, then it doesn’t need to be changed. It’s about removing barriers going forward.”

Shifting the Language

Overall, the word “disability” is often a misconception in itself. The disabled community embraces the term, Mantz says — it’s not something to dance around.

“From what I’ve seen, it’s more offensive to say ‘handicapped,’ ‘differently abled’ or ‘wheelchair-bound’ instead of acknowledging and accepting the person for who they are.”

It’s about person-first language, he adds. A wheelchair is a mobility device, just like a hand-cycle mountain bike is a tool to improve one’s quality of life.

“For me, I’m in the best shape of my life. My upper body is stronger and I’m healthier than I’ve ever been. The wheelchair allows me to do things I want to do. I think there’s a lot of negative misconceptions that people using wheelchairs need to get better, or the goal is to eventually not use them — but walking will never be a possibility for me, unless there’s some scientific breakthrough.”

Living life to the fullest, he says, means using a wheelchair. Reframing the context and language surrounding mobility devices could help dissolve tough barriers set in place by society.

“If those barriers are removed, then I can have a great experience, and I don’t foresee any challenges that anyone else would have when it comes to living a good life.”

The insight Mantz gained from his injury reveals a simple truth: regardless of our origins or past experiences, there is always a pathway to greater possibility. Sparking important changes means coming together in compassion for one another’s experiences.

“I think [accessibility] would give a lot of people a fuller life. And I think the RV industry can have a lead into making the outdoors accessible for everybody.”